The Life, Death and Meaning of Joe McCann

Deference and British militarism

In May the trial of two former paratroopers accused of the murder of Official IRA volunteer Joe McCann in 1972 collapsed. The news arrived mere months after Brandon Lewis’ announcement that there would be no further public inquiry into the 1989 murder of Pat Finucane. As I have previously argued in New Socialist, the current conservative administrations approach to retrospective justice in Ireland is coloured by the imperialist foundations of the modern British state. These foundations contribute towards a distinct aspect of the national character, one that is sharpened by the socio-economic recuperations and realignments that now constitute the received wisdoms underpinning post-industrial neoliberalism.

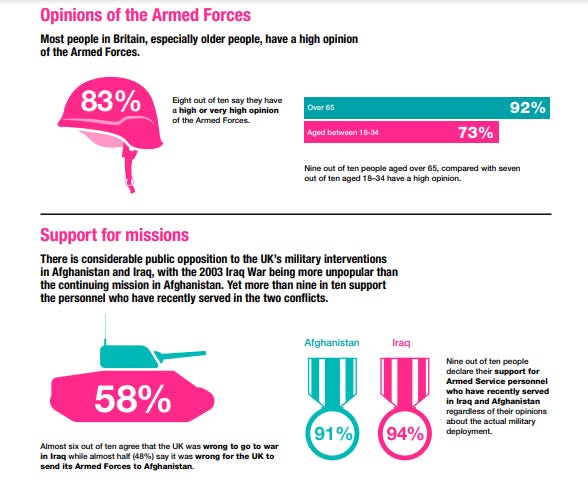

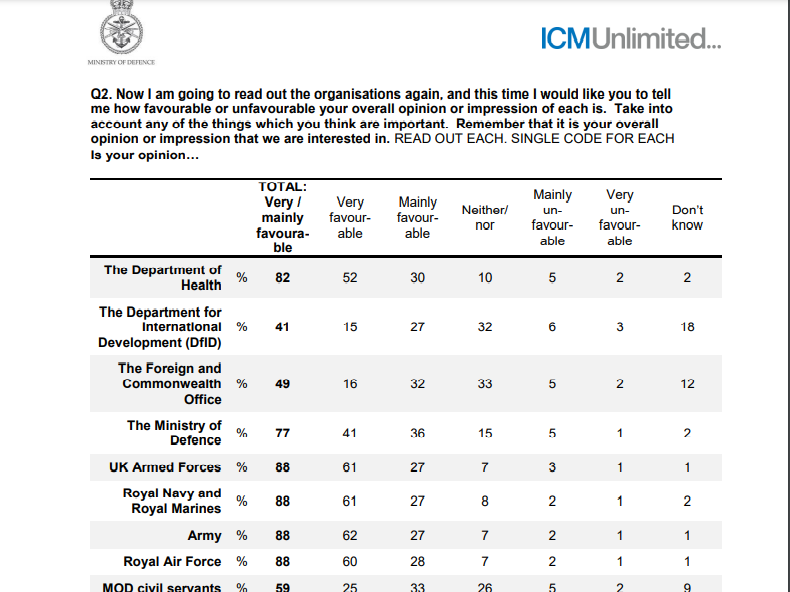

Positive attitudes towards the military and the increased visibility of the armed forces in various aspects of British public life have increased markedly over the last decade, albeit with much less enthusiasm for the troops most prominently disastrous missions in Afghanistan and Iran. The latter consensus originates not from any form of anti-imperialism or lack of enthusiasm for military intervention in general, but from the belief that terrorism and immigration are intertwined threats to national security and identity. In this light, positivity towards the armed forces (and the attendant fetishization and valorisation directed towards those institutions) is symbolic of a nationalistic deference to authority and the repressive state apparatus that defines a certain section of both liberal and reactionary ideology in Britain.

There has been enthusiastic acceptance of increased military visibility in everyday ceremony and commemoration in public life. Whether through the use of the armed forces at sporting and cultural events, the prominence of brands such as Help For Heroes on various ephemera and the collective, yearly descent into national psychosis encapsulated by debates and disgruntlement as to what specific size of Poppy - or particular expansion into commemorative tat - most accurately amounts to a sufficient public display of #respect.

There is a very specific brand of deference motoring the hamster wheel churn-to-nowhere that constitutes the yearly flashpoints of the culture war in modern Britain. At present, this is a culture war being waged almost entirely to the benefit of the forces of reaction. In one sense, such institutionalised deference has always existed. Arguably, it is among the defining aspects of the British state and a powerful subsection of the national psyche.

When people in Britain talk about the Troubles or Irish republicanism more broadly at all, especially with reference to retrospective calls for justice that might implicate members of the armed forces in torture and/or murder, these positive feelings towards the military are often cynically and ruthlessly bolstered to further entrench British nationalism and exceptionalism, guard against genuine reckonings with our colonialist and imperialist past and obscure the material reality of British rule in Ireland. Furthermore, they are used as a disciplining tool with which to delegitimise and caricature as untrustworthy individuals or societal groups who oppose imperialism and militarism.

What follows is an attempt to unpack the meaning and symbolism of the life, death and cultural afterlife of Joe McCann within these contexts. Part 1 will outline the basic biographical and historical facts of McCann's life and death, situating them within the early years of the Troubles and republicanism more broadly. Part 2 will analyse the court case brought against his killers and its collapse within the framework of the British imperial state and its attempts at historical and political revisionism.

"The Irish Che Guevara"?

In death Joe McCann would become one of the most totemic republican figures of the early years of the conflict in the north. In life, he had risen to the rank of Officer Commanding (OC) of the Official IRA in the Markets area of Belfast, a regional stronghold for the movement after the Provisional/Official split triggered by the upsurge in violence in the north after 1969.

No doubt McCann's decision to remain with the Officials, an organisation that would eventually go on to embrace a more formal (but always idiosyncratic and complex) relationship with Marxism and Marxist-Leninism, contributed somewhat to him being posthumously referred to as "The Irish Che Guevara" by some media outlets.

In reality, the comparison serves only to obscure the specificities of McCann’s life and the distinct material conditions that surrounded the conflict he was involved in. Thomas Sankara, the pan-Africanist Marxist revolutionary and president of Burkina Faso from 1983-1987, was often referred to as the “African Che”, a title that is at once every bit as reductive as that of the "Irish Che". But it was at least partially more accurate in one sense. Sankara, like Che, was involved in the business of post-revolutionary state formation, a core participant and eventual figurehead within movements that would, in however limited or brief a manner, fundamentally reverse power relations within their societies. McCann would never have the chance to contribute this level of individual influence on the everyday mechanics of a state after having waged war against its previous iteration. The Troubles would be far more protracted and drawn out than the conflicts that made Che and Sankara eminent icons of anti-imperialism.

McCann's personal comportment and military record played a more crucial role than his ideological affiliation. Despite the insinuations and accusations made by the Provisional IRA, as well as the British and Irish security services, Official republicanism didn't formally embrace Marxism until just under a decade after McCann's death, despite the influence of Marxist intellectuals such as Roy Johnston and Anthony Coughlan on the policy directions advocated by the OIRA and Sinn Fein leadership. After the split, the Official wing of republicanism would call a conditional halt to its armed campaign in May 1972, in part due to local outrage at the death of William Best, a Derry born soldier in the British Army who was killed during a return visit to his hometown on leave. During this period the OIRA distinguished itself strategically from the nascent Provisionals by adopting a policy of “defence and retaliation”, a strategy that would eventually put McCann at odds with his own leadership. The policy and its context are outlined by Derry OIRA man (and later co-founder of the IRSP in the city, as well as a leading INLA volunteer) Tommy McCourt, in the somewhat obscure (not to mention tonally inconsistent) 1973 documentary "No Go!":

By this stage the Official leadership was slowly beginning to factionalise over political analysis and military aspirations. The movement had begun to be outstripped in terms of both profile and membership in the years since the split. Defence and Retaliation was an attempt to accommodate the understanding that militarism alone, stripped of meaningful associations with broader social agitation, was limited in scope. Distinguished from the Provisionals policy of taking the fight to the British by initiating engagement and attacking pre-emptively, the Officials instead judged their role in their various Belfast strongholds - in particular the Markets - to be one of community defence in reaction to incursions and transgressions by the British, responding to each injury or casualty in kind (“returning the serve”, to use the Loyalist combatant David Ervine’s famous phrase).

Given the ceasefire and the eventual transmutation of its armed wing into the shadowy “Group B”, McCann’s legend might seem somewhat incongruous. While Provisionals studiously crafted an image alternative to that of the organisation they had split from - one more intrinsically equipped to deal with the day to day practicalities and challenges of urban guerrilla warfare than the Officials geographically and ideologically detached Dublin leadership - McCann was one of the figures Officials could point to as a rejoinder to Provisional claims of ineffectiveness and a lack of military dynamism on their part. At a time when those influenced by a more orthodox Marxist approach to stageist national liberation formed a highly influential cluster of Official republicanism, McCann was regarded as among the most militant commanders then operating. He was the subject of several internal IRA disciplinaries relating to his desire for a more proactive, muscular response than was possible within the framework of the Defence and Retaliation policy, being a prominent northern voice pushing the Dublin leadership to move more "gear" up the country: "on one occasion getting into a shouting match with the Officials Quartermaster General in Gardiner Street" (Hanley and Millar, 2010, Pg. 172-173)

Young, handsome and capable of instilling utter dedication to those in his charge, McCann’s legend is one slightly at odds with that of subsequent iterations of Official republicanism, evolving as it did into the ideological and organisational bureaucracy of a representative political party machine that denied entirely the existence of its armed wing (and eventually renounced republicanism altogether). He was considered by many (with the notable exception of some of his superiors) to be one of the Official IRA’s most talismanic commanders during this era.

The reasons for this are three fold. Firstly, McCann’s sheer force of personality and the numerous anecdotal evidence of his defiant and often extremely risky engagement with the Brititsh. Two incidents in particular stand out in this regard, both of them detailed by Brian Hanley and Scot Millar in their landmark history of the Official movement. While it is impossible to ascertain the veracity of the story, as is the case with all anecdotal evidence, there is little reason to believe it has been overly embellished. It is representative of the kind of spontaneous risk taking that made McCann a potent symbol of republican rebirth that chimed with an element of outlaw 1960's counter culture. It was also the kind of incident that marked him out as an increasingly unmanageable loose cannon in the eyes of some more senior republicans:

"His attitude was evident when he and a comrade were going to see the move Soldier Blue. While his friend studied opening times, McCann drew a handgun and opened fire on a nearby army checkpoint. Plans of movie watching were abandoned as McCann ran off laughing, his comrade roaring: "You mad bastard! What are you doing?" (Hanley and Millar, 2010, pg 167)

This tale above all others demonstrates McCann’s specific brand of charisma. As outrageous and erratic as we might consider this kind of behaviour, it was also easy to see how many Official volunteers and their supporters in republican strongholds would have drawn inspiration from their sheer unapologetic gumption. Similarly, while on the run in Co. Louth after internment was introduced in 1971, McCann not only regularly returned to Belfast (often against the advice and instruction of his own commanders in the Officials Dublin based leadership), but it is recounted by Hanley and Millar that he was spotted at least once "walking his pet wolfhound around an army base in Albert Street to boost local morale" (Hanley and Millar, 2010, pg 167).

10th August, 1971

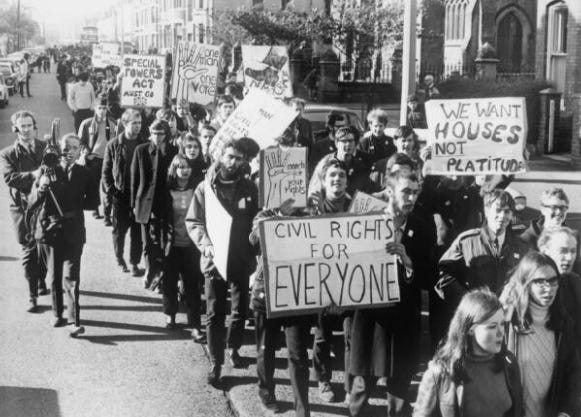

The second reason for McCann’s enduring legend is his role in the events at the Inglis Bakery in Eliza Street on the Markets during 10th August 1971. The day before, British troops had careened through nationalist areas of the north, ostensibly bent on scooping up active members of militant organisations as part of Operation Demetrius. In effect this was a hugely inflammatory, traumatising and violent event that interred without trial large numbers of non-combatant, civilian nationalists guilty of nothing more than being nominally catholic. British Army intelligence was outdated and inaccurate, with many of those lifted either retired entirely from republican activities or with no association with the modern iteration of militant republicanism at all. This included non combatant political leaders of civil rights organisations such as Michael Farrell, which further inflamed tensions and stoked a sense of arbitrary injustice. Subsequently, many of those interned were subject to violence and intimidation during interrogation in various prisons and holding centres.

These excesses on behalf of the British triggered some of the most violent disturbances of the early Troubles. In the immediate aftermath of the first flare up of resistance to internment, McCann led a unit of six Official volunteers in taking over the bakery and defended the position during an intense shoot out. Estimates vary as to the strength of numbers with regard to the British troops, but McCanns men were certainly outnumbered. Henry McDonald and Jack Holland report that there were up to six hundred British troops rotated around the immediate area, both directly and indirectly engaging McCann's unit for over 10 hours (Holland and McDonald, 1995, pg 12). Hanley and Millar provide some amusing colour:

"At one point the British announced that the gunman had been trapped and killed, only to be embarrassed when it was discovered all had escaped" (Hanley and Millar, 2010, pg 166)

At the height of the pitched battle a photograph was taken of McCann by Life Magazine's Terence Spencer - crouched down, rifle at his side, captured in silhouette as the starry plough flag of Official Republicanism flitted above him and fires raged.

The image remains an iconic one, still peddled on T-shirts, posters and all manner of ephemera. After its initial UK publication in the Daily Mirror, the image was splashed across a spread in Life Magazine, replete with captions that further cemented McCann’s status as a folk hero among a young generation of socially conscious post-’69 republicans. It also mainlined imagery and iconography familiar and evocative within the republican tradition since at least as far back as the Easter Rising.

The characteristically dramatic Life Magazine commentary further solidified the photos iconic status:

‘At right, crouched beneath the Irish Republican tricolor [sic], a professional IRA terrorist who goes by the name of Joe awaits a counterattack by British infantry during the battle of Eliza Street. “Joe was a tall, thin man who moved only in leaps and crouches”, reports Life correspondent Jordan Bonfante, who with photographer Terence Spencer covered the fighting last week. “He was an absolute hero to his men, mostly neighborhood irregulars, and as he directed them with grunts and waves of the American semi-automatic carbine he carried in one hand he looked as though all Ireland were at stake on Eliza Street.” For twelve hours before being surrounded and broken up, Joe and his men had effective control of the whole downtown market area in east [sic] Belfast.’ (quoted in Mulqueen, 2010)

The image was also included in the Sunday News, which contained the first reference to McCann as "the Che Guevara of the IRA" from correspondent Jim Campbell. Outside the mainstream media internationally, both the image and the connotations of the descriptor were leaned into by the Irish republican press. The United Irishman, the monthly organ of the Officials, displayed the picture on its front page that September alongside the now iconic headline: ‘Army of the People’, a phrase used by Official republicans in reference to their conception of themselves as a movement reflective of a broad based involvement in social campaigns and community activism (contrasting subtly but instructively with their reading of the Provisionals as unthinkingly hawkish and politically short sighted). ’ Yet as Sean Swan has highlighted, the United Irishman cover contrasts somewhat with the writing within that issue, much of which is more representative of the Officials future post-ceasefire trajectory. (Swan, 2008, pg 340).

An Phoblacht, the Provisional equivalent, also splashed the photo.

Imagery, romance and romanticism

At least a portion of the potency of the images symbolism lies in its composition. McCann’s wiry frame belies the strength of his posture, his position to the bottom left of the photo foregrounds a churn of flames and smoke in a manner that is dystopian, biblical and apocalyptic all at once. In terms of the images emotional affect, the faceless McCann becomes a cipher for both the courage and vulnerability of the wider republican community in Belfast.

For those politically opposed to the republican struggle and either sympathetic or outright deferent towards British militarism, this universality might be rendered sinister and malign, the enemy within basking in the embers their anti-British ideology has created. The image is romantic on the level of emotion and affect, tapping into not only historic republican self conceptions and the collective memory of a marginalised populace, but also romanticist in its composition: McCann is pictured amid a swirling vortex of the elements in a vein not dissimilar to the framing of romantic poets and artists throughout the previous century.

Outside of the terms cultural meaning, there is a literal romance contained within the image, one that would have been especially redolent and powerful in the immediate aftermath of the events depicted, especially within the well connected and close knit republican communities of Belfast. News travelled fast and anecdote quickly became legend. While we don’t know for certain at which stage in the fighting the photo was taken, the ambiguity of McCanns body language - it can be interpreted as either defiant concentration as to the task at hand or a break in the intensity of the shooting, with an awestruck McCann attempting to comprehend the enormity of unfolding events as they relate to both the specificities of place and the wider historical epoch he finds his city and his country engulfed in.

Republicans are often portrayed by their political opponents as mawkish sentimentalists, yet the photo is more accurately described as politically romanticist. It is an image grounded in the local (the text of the Inglis bakery sign is clearly visible in certain uncropped versions of the image) yet ripe for projection on behalf of the viewer. While it would be a stretch to present the photograph as some accidental riff on the paintings of Friedrich or Delacroix, there is an undeniable universal potency to the image of the kind that broadens the iconographic appeal beyond its immediate regional base. This is what catapults it into the wider world of distinct but interconnected anti-imperialist iconography of the post-68 period.

Early life and republican activism

Joe McCann had graduated from teenage involvement in Na Fianna Éirean to membership of the (pre-split) IRA in 1963. According to Malachi O'Doherty's account, McCann was recruited and sworn into the IRA by then Belfast OC Billy McMillen in the Ard Scoil building on Divis Street, "which was at the centre of Irish language teaching and gaelic culture in Belfast at the time". McMillen, who was infamously assassinated by the then still teenage future INLA and IPLO leader Gerard Steenson during the intra-republican bloodletting of the Official/INLA split, had previously made contact with the breakaway Saor Uladh organisation before gravitating back to the IRA in 1961 after being interned.

Although he would become indelibly associated with the Markets area of Belfast, McCann was born on the lower Falls on 2nd November 1947 to Joseph and Jane. Joe shared both a name and an occupation with his father, who worked on building sites as a bricklayer. Both parents were themselves lifelong Falls residents. Jane died in 1953 when Joe was just 5 years old, survived by Josephs senior and junior as well as another brother and two sisters, Joe jr being the eldest.

The family eventually moved to the newly constructed Highfield estate in West Belfast, where McCann was said to have mixed well with protestant students and neighbours. Joe passed his eleven-plus and was accepted into a Catholic grammar school, St Marys, an institution from which he would eventually be expelled. While there is no conclusive administrative record as to the specifics, there is some conjecture that McCann's gradual politicisation may have put him at odds with the Christian Brothers running the school. This nugget of information, generally ascribed to family mythos, is made all the more intriguing by the fact that religious interest and a degree of faith remained an important facet of McCann's character throughout his life, making him something of a microcosm of the tensions and contradictions within republicanism after the conclusion of the 1956-'62 Border Campaign.

Given both his expulsion from St Marys and the posthumous eulogising of McCann as the supposed embodiment of an increasingly Marxist oriented OIRA, its worth remembering the influence of radical liberation theology on his political outlook. In his entry on McCann in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, Brian Hanley fleshes out this aspect of McCann's thinking:

"Though sympathetic to socialism, he was a member of the Third Order of St Francis, a lay branch of the Franciscans. He was influenced by the journal Grille which sought to fuse left-wing thinking with radical Christianity."

By 15 years of age he was apprenticing in his fathers trade, by that stage having accrued three years of experience in the Fianna as his interest in Irish history, politics and cultural pursuits mushroomed. In 1964, his family having relocated to Turf Lodge, he became involved in the IRA proper, participating in the riots that flared up in the aftermath of the RUC removing the tricolour flag from the election offices of Billy McMillen in Divis Street in 1964. He was also involved in opposing British army recruitment in schools. In October 1965 he was involved in an incident at a North Belfast school in which he and a group of young activists disrupted the British military presence at a careers fair.

It possible that McMillen's dissatisfaction with the IRA's strategic and ideological direction with regards to its military aims in the post WWII period, coupled with his generally generally solid support for the organisations Marxist influenced strategy of social agitation in the regroupment after Operation Harvest, would have impressed upon the young McCann a sense of purpose and direction. McCann certainly seemed to embrace this new front in republicanism, and while firmly predating the later influx of "69ers" to the movement, seems to have recognised a need for modern, "fit for purpose" republicanism that addressed not only questions of national sovereignty but class politics. He is recorded by Gerry Adams as having been impressed by OIRA Chief of Staff Cathal Goulding's Bodenstown address in June, 1967, a speech that implored republicans to become involved with social movements, protests and pickets throughout the province, with a particular focus on the activities of the then highly active National Farmers Association. (Adams, 1996, pg 82)

Details of McCann's involvement in military activity and social protest in the year or two following his formal IRA membership are scant, but we do know that in 1965, then aged 18, he was one of the "five silent men" from Belfast who refused to speak or give any evidence at their trial for possession of weaponry (in this case some largely symbolic bayonets) and documents detailing RUC membership and activities (Hanley and Millar, 2010, pg 46). If Adams account of McCann's legend is to be believed, the men (of whom McCann was already an acknowledged and respected leadership figure amongst), refused even to disclose to priests during confession their intentions in terms of the bayonets.

In 1969, during a Peoples Democracy/NICRA march in Newry responding to Loyalist violence during the ambush at Burntollet on January 4th, McCann was present, alongside a significant portion of the Belfast brigade, as stewards. Incensed by the brutality and collusion on display at Burntollet, the Newry marchers responded more militantly to police attempts to reroute them. A riot ensued, with McCann last seen driving an RUC van into a nearby canal before his arrest along with 24 others (McCann, Joseph (Joe) | Dictionary of Irish Biography, 2021).

On 13th August McCann was responsible for directing the orders of McMillen in response to the outbreak of the Battle of the Bogside in Derry, with IRA units in Belfast ordered to "get people onto the streets" to "take the pressure off Derry". At the head of a crowd of 1,000, McCann and his fellow volunteers surrounded an RUC station in Hastings Street, where it was believed police were assembling to be redeployed to Derry to combat the Bogsiders resistance. Windows were pelted with stones and broken while the door was rammed and various tactics, including the use of strategically deployed nails and whitewash were used to hamper police progress. Several IRA members were also armed during this direct action, responding to the RUC tactic of driving armoured cars through packed streets to clear them by firing rounds in response, wounding one RUC man. He is also thought to have been a member of the IRA active service unit that defended the area against a Loyalist incursion later that day, firing on those advancing towards the rioters. These events would lead to his imprisonment under the special powers act on 20th August.

While there is no detailed record of McCann's reasoning, he remained loyal to the Dublin leadership of the faction that would eventually become known as the Officials after the split in the movement following the famous confrontation between several veterans in the north and their younger allies with McMillen in Cyprus Street in September of 1969. When it was discovered by those who had led the confrontation that McMillen, having made a few concessions where he could, was still in touch with (and had no intention of breaking with) the Dublin leadership (whom the complainants accused of strategic and resource based neglect of their units in the north), the nascent Provisional breakaway began the task of organising themselves as a new and separate organisation. It is around this period that McCann was promoted to a position of command within the OIRA in the area.

Despite not being a native of the area, as an IRA man McCann would become firmly associated with the Markets, a part of the city in which the Officials carved out perhaps their most notable stronghold. The writer and Guardian/Observer correspondent Henry McDonald has recounted on more than one occasion McCann using his family home in the Markets as an informal safehouse. An interesting detail in "The Lost Revolution" is the confirmation that the Markets OIRA unit of which McCann was OC was the designated brigade for radicalised recruits from Queens University, the vast majority of whom hailed from middle class backgrounds that contrasted starkly with the everyday experiences of working class nationalists, especially that of working class nationalists living in the densely demarcated flashpoints between republicanism and loyalism that typified the urban geography of working class Belfast.

One of the most notable of those student recruits was Ronnie Bunting, son of Loyalist hardliner Sir Ronald Bunting (who was heavily involved in the ambush at Burntollet) and future leader of the INLA. McCann is recorded as having had a slightly less suspicious view of the involvement of middle class graduates in physical force republicanism than some of his fellow working class peers in the republican movement. Given the Officials insistence that their commanders embrace social campaigning in tandem with their military roles often meant participation in local campaigns with a cross-class coalition of nationalist sympathisers, and the Markets units designation as the entry point for Queens graduates, McCann would have been a prominent link between these two differing socio-economic bases. Certainly his youth and appearance marked him out as a far more contemporaneous looking republican figure. Both the photograph of him on a march from Queens to Belfast City Hall in October 1968 that was comprised largely of students and a police mugshot snapped 10 months later depict a young man of relatively neutral sartorial taste that could nonetheless be interpreted as folding into a certain subsection of post-beatnik countercultural style.

The association with future INLA chief Bunting is also notable. There is enduring speculation as to whether McCann would have eventually left the Officials in favour of the breakaway organisation spearheaded by Seamus Costello after his dismissal from the ranks of the Officials (Holland and McDonald, 1995, pg 15-16). Costello had been responsible for the establishment of a small active service unit of Official volunteers operating along the border region after internment, of which McCann was a member. This presumption is further bolstered by McCann's analysis of the situation in the north requiring a more pro-actively militant response and the Dublin leaderships gradual drift towards ceasefire. The Officials subsequent ideological direction on the subject of the conflict in the north and retreat from a traditionally republican analysis of the war in the north as one of national liberation was seemingly at odds with McCann's. However, McCann was far from a traditional republican militarist who considered politics the terrain of the compromised. His vision of republicanism clearly dovetailed with the Marxist influenced analysis of the primacy of social and economic campaigning.

Certainly its not difficult to imagine an alternative timeline in which McCann survived and went on to become a prominent advocate for something approaching the Costello factions conception of the necessity of a national liberation front, itself an idea rooted in the global experience of resistance to colonialism in the post-colonial Cold War era. This possibility, coupled with McCann's increased risk taking and refusal of disciplinary orders imposed on him by his superiors, has led to speculation that the Officials set him up to remove one of the most charismatic and committed adherents of a more militant approach as more influential figures within the leadership begun to favour a ceasefire. While this was the opinion of Anthony and Collete Dornan, McCann's brother in law and sister, it is worth noting that this accusation was dismissed outright by other members of McCann's family after his death (Swan, 2008, pg 350).

Joe McCann's death coincided with a brief scaling back of OIRA military activity across certain sections of Belfast. The hope had been to scale back activities in areas in the city that had arrived at a comparative level of stability in the months since internment had been introduced. The OIRA leadership was keen to return to social movement base building and reinject a level of non-violent resistance into their campaign, in line with the policies of social agitation undertaken in the years since the end of the Border Campaign. The killing of McCann would signal an end to this fleeting decrease in violence.

Still on the run, McCann had attended a wedding on the Falls Road at the start of April 1972 and only just avoided the grip of Special Branch in the city centre in the weeks after. On the 15th April his luck ran out. Having been spotted by a group of detectives on his way through the Markets to a pub where he was due to meet a friend, paratroopers were alerted. Although McCann was unarmed, it is said he thought it unlikely he would be taken alive by the British in such a scenario, which led to him fleeing the scene. His reputation among the paras was as one of the most militant commanders in the north. Already considered one of the most wanted OIRA operatives on the entire island, there was also the fact that he was suspected of involvement in the action that led to the first British casualty claimed by the OIRA in Belfast on 21st Mat 1971, when McCann's unit had engaged with a mobile patrol unit in Cromac Square. 7 weeks prior to his death the OIRA had claimed responsibility for the bombing of the headquarters of the British Army's 16th Parachute Brigade in Aldershot, an attack which injured 19 and killed 7 (most of them civilian contractors working at the HQ). The bombing was in retaliation for Bloody Sunday, which had occurred three weeks earlier. It marked the largest OIRA attack in Britain of the entire Troubles, as well as one of the last major OIRA actions before their ceasefire in May. McCann was also suspected of involvement in an attack on John Taylor, the Minister of Home Affairs at Stormont, who was raked with gunfire from an OIRA ASU in Armagh on 25th February (although, incredibly, Taylor survived). In this context it isn't difficult to understand McCann's motivation for fleeing. Mcdonald and Holland detail the events that subsequently unfolded in the opening chapter of their history of the INLA, "Deadly Divisions":

"When he (McCann) saw the patrol he made a run for it and tried to get off the street by pushing at doors with his shoulder. None opened. He reached the corner of Joy Street and Hamilton Street when the patrol cut him down. A local shopkeeper counted ten spent cartridges near his body" (Holland and McDonald, 1995, pg 13).

Yet a subsequent pathology report claimed McCann was hit just three times. Given the shopkeeper was adamant that the shell casings outside their premises were discharged from just one soldiers weapon (who they depicted as kneeling outside their shop to take aim), and the fact that bullet holes were later found in the walls of houses on both sides of Joy Street and Hamilton Street, it seems unlikely that McCann was fired upon as few times as the army later claimed, nor that it was such a clinical operation as they presented it (the pathology report that emerged after the killing claimed McCann had been hit just three times, with only one of those wounds being fatal).

Ballistics tests were not undertaken in the aftermath, essentially meaning that it would have been impossible in any case to assign any of the rounds to individual soldiers. Whether or not this amounts to a deliberate policy of disinformation and cover up can be debated, but what is inarguable is that the pathology report was one that favoured the British army version of events and painted them as far less zealous and vicious than they likely were in reality, a consistent trope throughout the conflict that enabled the British to cast themselves as peacekeeping arbiters, with such excesses the preserve of the respective paramilitaries.

News of McCann's death sparked outrage and violent resistance in Belfast and beyond. Hanley and Millar cite the British estimating their troops came under fire at least 84 times in Divis Flats alone in the immediate aftermath, with one British soldier killed by OIRA D Company, Second Battalion whose area of operations took in the flats themselves. Barricades were erected in Ballymurphy, Andersonstown, the Falls, and Turf Lodge, which essentially became a no-go area for British troops. The famous photoghraph of an OIRA "Mobile Patrol" unit making the rounds in Turf Lodge in a modified Land Rover was taken during this period. OIRA units carried out sniper attacks and ambushes in Newry and Derry, with two soldiers killed in the latter.

Joe McCann's funeral took place on the 18th April. The crowd was described as one of the biggest in the history of republican mobilisations in the north of Ireland, with estimates ranging between 5,000 and 20,000. This number included the MP's Paddy Devlin, Paddy Kennedy, Paddy O'Hanlon and Bernadette Devlin. There is some discrepancy in accounts as to the amount of formally identifiable OIRA volunteers involved in the funeral proceedings, with Hanley and Millar identifying 21 OIRA companies leading the cortege and marching in formation. McDonald and Holland simply refer to the presence of "over twenty Official IRA men". The procession was followed by hundreds of women carrying wreaths and was unparalleled in terms of its size, exceeded only by the funeral of Bobby Sands in 1981. McCann's Irish wolfhound, the same pet he had once defiantly walked past a Brtish army base in the city a few years earlier, walked at the head of the cortege. It had not been unknown for McCann to make use of his country wide contacts in the Irish Kennel Club to shelter while on the run during his IRA service.

Cathal Goulding gave the oration (he can be seen at the end of this AP video of the funeral).

Severalile Irish writers posthumously assessed McCann's status as an early republican folk hero of the Troubles. For the journalist, author and trade unionist Padraig Yates (once himself an OIRA volunteer), McCann was: "an incredible character, the only genuine hero I ever met out of the Northern troubles". Kevin Myers was struck by his "curiously ironic and knowing sense of humour" (Myers, 2006, pg 74-75) as well as regarding him as "incredibly handsome". Outside of the republican milieu, Malachi O'Docherty recalls the consensus from the socialist and communist left - many of whom tactically or ideologically opposed the Officials armed campaign - was that McCann was 'a very likeable fella' who was open to "good discussions" (O'Doherty, 2019, pg 126–7). McCann's likability within republican circles also breached the increasingly fractious divide between Provisionals and Officials. Republican News, a Provisional outlet, also described him as a 'man of the people'. (Republican News, 23 Apr. 1972).

Prior to McCann, the two most prominent republican martyrs in recent memory were Seán South and Fergal O'Hanlon, who died in 1957 from injuries sustained during a new years day raid on an RUC station in county Fermanagh as part of the Border Campaign. Just like those men, McCann's life and death became the subject of poems, paintings and songs, most notably Christy Moore's setting of an Eamon O'Doherty poem to music.

A plaque commemorating him was unveiled in the Markets in April 1997, an event which attracted all strands of erstwhile oppostional republicans. He was survived by his wife Anne and their three children Fergal, Aine and Fionnuala. His son Ciaran was born shortly after he died and this is the familial unit that has subsequently campaigned for justice for the best part of five decades. It is that campaign, and the response of the British political and media class, which will be analysed in detail in the second post in this series.

96. Beforehistory of the IRA. London: Verso.

Hanley, Bthe Dawn: An Autobiography. Brandon.

Finn, D. and Millar, S., 2010. The Lost Revolution. London: Penguin Books.

Holland, J. and Mcdonald, H. (1995). INLA - Deadly Divisions : the story of one of Ireland’s most ruthless terrorist organisations. Poolbeg Press.

Mulqueen, J., 2010. ‘The Che Guevara of the IRA’: the legend of ‘Big Joe’ McCann. History Ireland, [online] (1 (Vol, 18). Available at: https://www.historyireland.com/troubles-in-ni/the-che-guevara-of-the-ira-the-legend-of-big-joe-mccann

Myers, K., 2006. Watching the door. Dublin, Ireland: Lilliput Press

O'Doherty, M., 2019. Fifty years on. Atlantic.

McCann, Joseph (Joe) | Dictionary of Irish Biography. [online] Available at: https://www.dib.ie/biography/mccann-joseph-joe-a10141